Over the years of building BillionBricks, I’ve observed many startups initially try to address the housing crisis but end up pivoting to high-end housing as the pressures of survival and the need to seek strong business opportunities take precedence. My recent encounter with a startup was my first time witnessing such repositioning in close range.

“It’s nice to finally meet you in person, Prasoon,” said Tony*, the CEO and founder of a prefabricated homes startup, while shaking my hand. We casually chatted about my flight and commute as he led me inside their huge shed – a manufacturing plant slash showroom.

A couple of months ago, one of the startup’s board members approached me at a conference where I served as a guest speaker. He wanted to set up a meeting between me and their CEO, as he believed that our companies’ visions overlapped and we could possibly partner for upcoming projects.

The board member’s assumption was not unfounded. In fact, I was already quite familiar with the startup because it joined the same accelerator program that BillionBricks also participated in two years ago. I’m always open to collaborating with like-minded individuals and firms, so when Tony called to introduce himself and set up a meeting, I was not one to say no.

I’ve heard much about Tony and his reputation as a young trailblazer who built a successful bootstrapped business offering sustainable tiny homes. Meeting him face-to-face, he looked and acted more mature than his age; mid to late 20s, I was told.

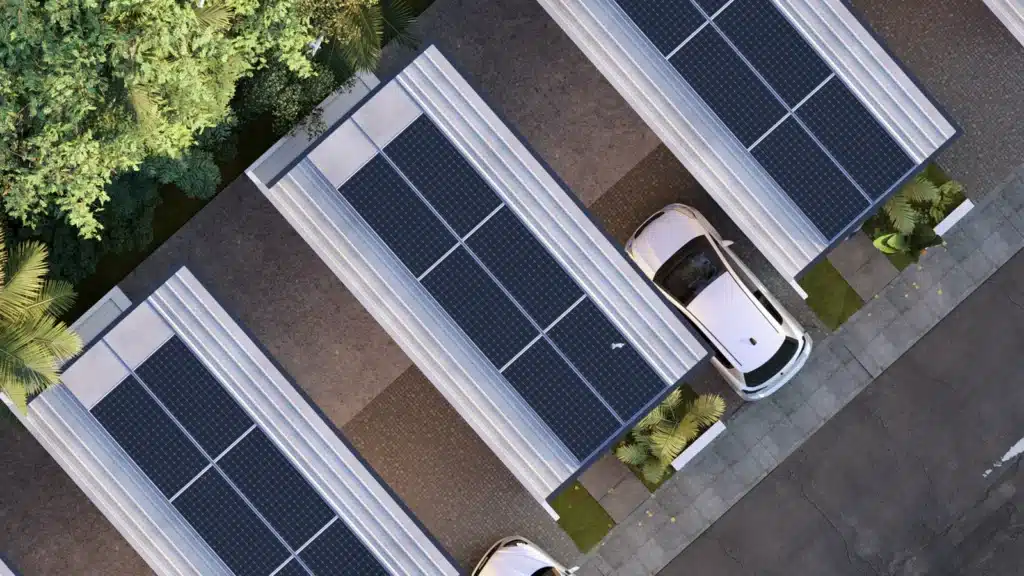

As we passed through the factory where they make roofs, walls, floors, and other fixtures, I was deeply impressed. I thought to myself, this is what I had envisioned for BillionBricks, and here is a guy who has actually done it while I’m still contemplating on how to do it.

Tony ushered me to a standing model of their best-selling product: a 29-square-meter home complete with a loft bedroom, a tiled bathroom, a kitchen, an office-cum-dining area, built-in storage, and impressive furnishing.

The unit’s sleek and minimalist aesthetic made it nice enough for an HGTV feature, and the price tag attached was equally luxe – a little under USD 40,000, all-inclusive. The unit can be delivered and assembled on-site in a matter of hours, ready for occupancy.

Tony started the business with the vision of solving the housing crisis. Like BillionBricks, his startup sought to offer affordable housing – reasonably priced adequate shelters that low to moderate-income families could afford. But when Covid-19 hit, they needed to pivot fast to seize an opportunity; doing so propelled the startup to evolve and serve the high-end market. Instead of providing cost-efficient houses for those who couldn’t afford dignified shelters, they came to manufacture playhouses for the rich.

Tony’s situation was in line with my theory and many other case studies showing that housing startups, at some point, do end up recalibrating. So far, no one – including BillionBricks – has cracked the code on affordable housing vision and market.

What impressed me, however, was Tony’s aspiration to return to the founding roots of his housing startup. In contrast, many ventures that pivoted to expensive homes show no desire to go back, all the while continuing to sell their original vision like bait to gain praise and attention and feel good that they are on an honorable mission — one which, in reality, they have already quietly aborted.

“I’m quite upset that we ended up here,” Tony lamented. “I want to shut down this high-end product and reboot the business to return to our vision of providing affordable housing.”

Before meeting Tony, I had been pondering over possible ways we could collaborate. Considering the pressures that weighed down my shoulders and how long it would take us to build our first affordable housing community, I also thought about the possibility of BillionBricks launching a high-end house to see early sales and show signs of success.

I thought it would be nice to co-build a product and make the most out of Tony’s experience in the high-end market. However, he surprised me by looking up to BillionBricks with the assumption that we have cracked the affordable housing market and that we could help them get into it as well. We both seemed to be trying to latch onto each other’s success. In some ways, it was an ideal foundation to build a partnership.

Tony shared that they wanted to focus on offering a more cost-efficient house at USD 12,500 and were looking to partner with BillionBricks to penetrate the lower end of the market. His intention to forego profit for passion was admirable, but I wanted to play the devil’s advocate.

“Your best-selling product is a cash cow, and, strangely, you want to shut it down. If you’re selling 50, 60 units of it now, why not scale it and sell 500 to 600 units before scrapping it?” I grilled Tony.

“No, man,” he shook his head. “Like I told you, I want to be true to our vision. It’s more important than the margins.”

Being true to one’s vision. You got to respect that. Having established that our visions aligned, I told him that we’re building a 1,000-home affordable housing community and that our startups could collaborate.

His eyes lit up at our scale of work and ambition. We were both excited and left on a positive note, agreeing to meet again in a week with more clarity.

– – – – –

I took charge as we sat down for our second meeting. Tony mesmerized me with his vision the first time around. But I knew the nitty-gritty of the affordable housing sector better and took the liberty to explain to him the financial model, target price points, and other practical details that needed to be discussed. As we dug deeper into the topic, Tony seemed clueless about the affordable housing market.

“Here’s the thing: our budget is USD 18,000 per unit, which is half the price of your best-selling product,” I stated matter-of-factly.

“And our houses are 43 square meters – that’s 32% percent bigger than your product.”

Tony was taken aback the moment he heard the actual numbers. He might have expected their margins to be reduced but not substantially slashed off like this.

The idealism that the young CEO exuded during our first meeting seemed to have dissipated; collaborating with us meant they would need to produce larger houses with a smaller margin.

And just like that, it seemed that being true to one’s vision wasn’t as important after all.

Startups’ Profitable Pivot from Idealism to Pragmatism

Tony isn’t the first startup founder in the housing sector to pivot from idealism to pragmatism.

Over the years of building BillionBricks, I’ve observed a few startups initially try to address the housing crisis but end up producing high-end housing for profit. As they got deeper into operating a profitable business, it became harder for them to go back to their roots.

For instance, I’ve seen a San Francisco-based startup that initially aimed to solve the housing crisis eventually offer tent pods with smart controls, memory mattresses, and other accessories available for rent and sale. At a starting price of USD 17,500 per pod, they’re a hit among glampers and short-term event organizers.

I’ve also observed another housing startup headquartered in Texas shift gears from its vision to serve the homeless and the poor. It collaborated with an architecture firm and a hotel mogul for a 3D-printed campground hotel project that offered stunning mountain views starting at a staggering USD 900,000.

Yet another startup based in California also caught my eye as it originally sought to address the housing shortage. After a while, it became known for building backyard studios, also marketed as custom offices and guest houses, with each unit starting at USD 200,000.

These three startups have one thing in common: they worked to solve the housing crisis earlier in their existence but later became very commercial, focused on a high and narrow market. This space is littered with numerous other examples of startups, all of which have failed at their original mission – they either perished or pivoted to serve the very rich.

That said, Tony’s shift in priorities didn’t surprise me. It was, however, my first time to witness such repositioning in real-time, right before my very eyes.

During our meeting, I went through the whole economic process of how much it costs to deliver a house. I explained our business model and how the margins can be very thin.

Tony, in turn, explained that their lower-end USD 12,500 houses are actually much smaller and had lower specs than their best-selling USD 36,000 homes.

“In reality, your lower-end homes are not more affordable. They’re just smaller,” I comment. “Your clientele may not change, so it’s not in line with your plan of rebooting your business.”

From there, our conversation went farther and farther away from a possible collaboration.

I initially agreed to meet Tony with the hopes of giving his startup the opportunity to tap the lower end of the market through us and, in return, get BillionBricks a chance to penetrate the higher end of the market, which was their zone of familiarity. A synergy of equals.

But it shocked me to realize that he wasn’t interested in what BillionBricks had to offer after all. He simply wanted to use us as a gateway to tap a new market, and while at it, he looked down on us as nothing more than a solar contractor.

Towards the last minutes of our second meeting, his line of questioning got somehow offensive.

“Why should we go with BillionBricks and what is it that you offer?” Tony challenged me. “Why shouldn’t I go to another solar roof manufacturer?”

At that moment, the situation became crystal clear. I was a startup founder looking for a potential partner with whom we could accelerate our collective vision to solve the housing crisis; he was a client looking for a vendor who could provide access to a market but on his own terms, not the market’s terms. We were not on the same page.

It was weird that he ended up probing me. He was, after all, the one who invited me to meet.

Problem-Solving Comes at a Financial Cost

My meeting with Tony reiterates why problem-solving is so hard: it comes at a financial cost. If you’re trying to solve a problem – and I mean really try to do it and not just exploit the appeal of problem-solving to launch a business – you need to look at the larger picture. It goes far beyond the margin.

Having followed fellow housing startups throughout the years, I’ve seen three reasons why founders lose their vision to solve the housing crisis.

First, diluting a brand is difficult once it has gone neck-deep into serving a certain market segment. For instance, ventures that have grown popular in the high-end market find it almost impossible to serve the low-end market because doing so will cannibalize their business with upscale customers.

Second, founders often deal with greater pressure from more stakeholders as the business grows and raises capital. After all, investors often want to see results quickly and may push the startup to focus on metrics like revenue growth. This can drive the startup to lose sight of its original mission and become more focused on short-term gains.

Lastly, I think some founders get derailed from their initial vision because the problem they’re trying to solve is simply too difficult. Addressing complex problems often requires a lot of resources, effort, and time, and founders can get discouraged or overwhelmed along the way.

As one might have guessed, my meeting with Tony didn’t end well. But before parting ways, we agreed that I would email him the drawings and specs of what we expected from a USD 18,000 house, and so I did. His reply was unsurprising:

After careful consideration, we can’t manufacture the unit type within your budget. Unfortunately, we won’t be able to proceed with a partnership at this time. Maybe we can revisit this again in the future. I wish you and your team all the best.

Four sentences. One unsuccessful match. No bridges burned.

A lot of startup founders aspire to do what BillionBricks is trying to do – solve the housing crisis while being kind to the environment. Sadly, in many cases, business interest eventually takes precedence. Despite this, many startups continue to talk about their mission to solve problems, even if they are not actively working towards that goal any longer.

But I believe that startups must practice what they preach. They must demonstrate their commitment to the problem they’re trying to solve amid pressure from investors and other stakeholders. Only then can they claim to be true to their vision.

Fortunately, BillionBricks is still surviving and has come to find the right stakeholders. How long we can keep up before we either perish or pivot remains to be seen. But if we can succeed, it would be a heck of a story – and a heck of a story to tell.

*Names have been changed to protect people’s identities