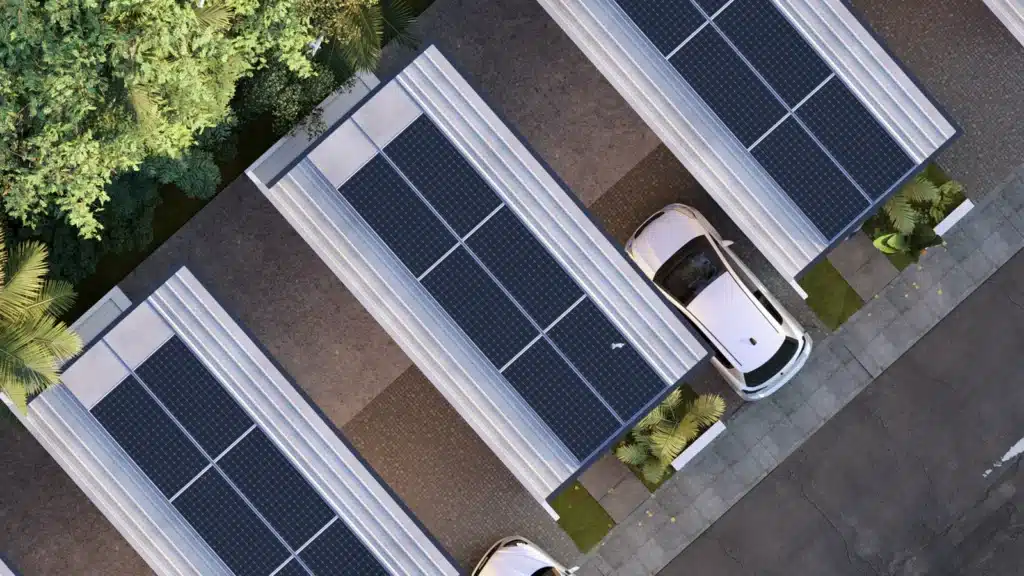

PHOTO: Rene Asmussen via Pexels

There is no shortage of opinions on how to solve the affordable housing crisis. In a perfect world, we would find a solution that would provide housing to those in need in a way that is socially, financially and environmentally sustainable. But as is true of most things, there isn’t one perfect solution.

I’ve noticed that one commonality among many proposed housing solutions is the shockingly low prices of the proposed housing models. Their costs defy all market-based sensibilities. While it is tempting to pursue these optimistic solutions, I don’t believe they are feasible in today’s market.

I’m an architect, and in my 10 years of working across commercial design firms, I designed over 10,000 houses for people who already had a home. A few years ago, I quit my job and founded a nonprofit innovation studio with a vision to end global homelessness. Our premise was simple: to question the current approaches and solutions around affordable housing.

For example, I recently saw a post from an urbanism and housing expert who believed reducing the cost of a $19,000 house listed on Amazon to $5,000 would solve the affordable housing crisis. Coincidently, just a few days before this, I was referred to another expert who had challenged the attendees at a forum to urgently come up with a cheaper housing solution. However, I believe the answer to the housing crisis isn’t as straightforward as lowering the cost of constructing a house.

I live in a 65-square-meter apartment in Singapore that costs $350,000. Is it cheap? No. Is it affordable? Yes. From my perspective, affordability is a function of the market we are in, and the market’s confidence allows us to stretch our dollar to what it deems is affordable.

Most market-based products are unattached to the cost of the good but driven by the buyers’ ability and desire to pay for it. In the case of affordable housing, however, the cost of constructing the house is considered to be most overbearing. We seem to look for a market-based solution by ignoring the fundamental principle of what drives a market: affordability.

We become so focused on this cost that we start neglecting necessities of what makes a house. I found a prototypical $3,000 house in an affordable housing dossier that had no kitchen, toilet or even plumbing. Many such examples ignore structural safety, profit margins for material suppliers and contractors, management costs and taxes. The real cost of these houses is kept hidden, while the artificial cost is used to sell the dream.

Since the private sector can’t function on hidden costs, the affordable housing sector has always remained out of bounds. Governments can do this job since they have many legitimate instruments to hide their real costs, such as subsidies. Then there are nonprofits or charities that can cover their real costs in philanthropic and other donation-based instruments.

Habitat for Humanity, the largest housing nonprofit, for example, has incredibly complicated and yet highly successful financial models. In 2018, the organization helped build or rehabilitate houses for more than 87,000 individuals across the world, which is not an easy feat by any means. But, contrast this with the estimated 150 million people who are homeless worldwide. We would still need hundreds of organizations with the creativity and scale of Habitat for Humanity. Since Habitat for Humanity was founded more than 40 years ago, we haven’t added many to this list. What makes us think that things will change now?

I believe this can change if more leaders and entrepreneurs come forward to innovate and disrupt the affordable housing market. Considering the complexity and higher upfront capital needs, the barrier to entry for most entrepreneurs is too high. Even capital is limited, as housing requires a long-term perspective, rather than a quick exit. Overcoming these barriers requires creativity, bold ideas and a little bit of foolish bravado. Entrepreneurs who are driven to solve real-world problems have these characteristics in abundance.

When looking for relevant benchmarks, look at other hardware startups or startups in medicine and bioengineering. They all commonly have long gestation periods, unlike the typical technology startups that are often seen in the limelight and used as examples to follow.

Once you have taken the plunge, simplify, and pick just one critical problem you wish to address to avoid overwhelming yourself with solving too many intertwined problems. Remember to empathize with the chosen problem, and go deep into solving it before addressing broader communal needs and establishing far-fetched goals that might set you up for failure. Go with the humility that the problem is too complex to be solved in its entirety, and focus on what matters to you the most.

I would argue that in our desire to find a “cheaper” solution, we are missing out on finding the most appropriate solution. People who struggle with homelessness are losing that battle every day, so it’s critical we avoid squandering our efforts on solving the wrong problems and instead focus on solving the right ones.

This article was originally posted by the Forbes Nonprofit Council on Oct 10, 2019 here.